Organics

Once found mainly on the plates of California hippies and Vermont back-to-the-landers, organics are now a mainstay of many American diets. The fastest growing sector in the food industry, organics now account for some 4% of food revenues, and reached nearly $40 billion in sales in 2014. But as organic products have moved from niche to mainstream, big corporations have moved rapidly to capture more control over the business.

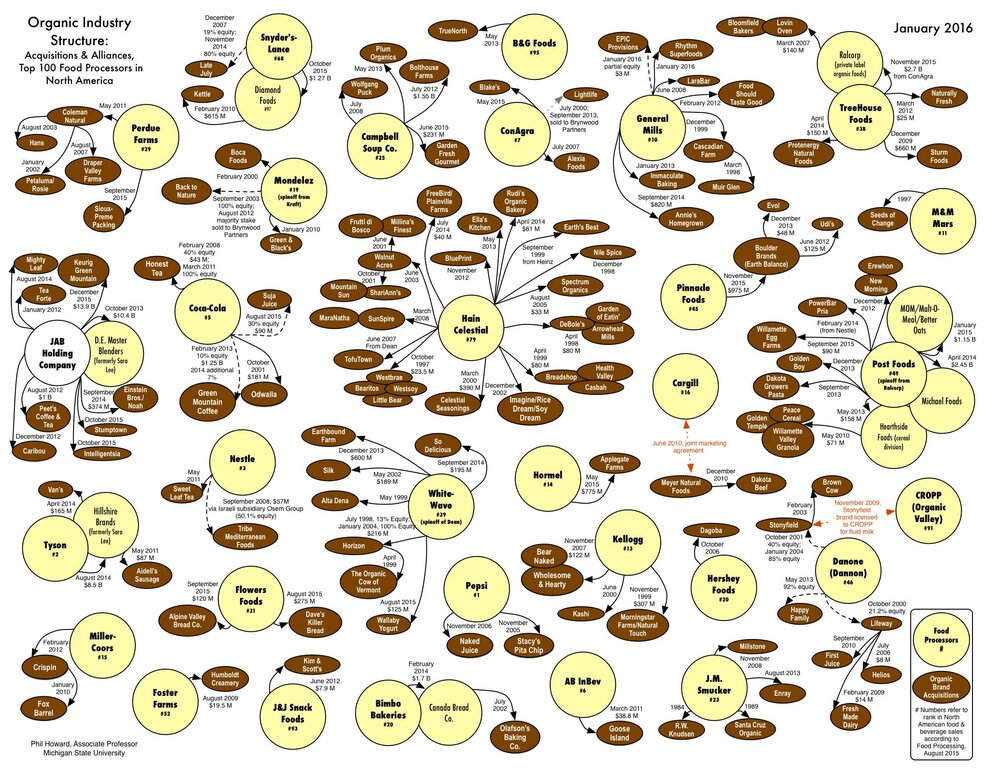

In recent years, a steady stream of mergers and acquisitions has concentrated control in the hands of just a few processors. Many brands that consumers believe to be mom-and-pop businesses are in fact now owned and managed by giant parents: Horizon Organic is owned by Dean Foods; Arrowhead Mills by the Hain Celestial Group; Stonyfield by Danone; Cascadian Farm by General Mills; Applegate by Hormel. Outside the most niche and expensive organic grocers it has become increasingly difficult for shoppers to find products from independent organic producers.

Read More

This chart, from Michigan State University’s Phil Howard, shows the extent of such concentration in the organic industry:

This concentration of power has also led to fear that the large companies will seek to erode organic standards. Congress passed the Organic Foods Production Act in 1990, calling for a federal standard for organics, and the United States Department of Agriculture’s National Organic Program (NOP) standards were implemented in 2002. On the surface, the requirements of the NOP seem very straightforward. To be certified as organic, produce must be grown without certain types of pesticides or genetically modified ingredients, and cannot be irradiated. Organic livestock, meanwhile, must be raised largely outdoors on 100% organic feed, and cannot be fed growth hormones or antibiotics.

But arguments about the fine print of the standards – especially concerning which additives organic farmers should be able to use – have persisted ever since, including a 2015 lawsuit over the process by which the USDA approves organic additives. Many farmers and consumer advocates believe the organic label doesn’t go far enough to ensure that organic producers actually uphold environmentally sustainable growing practices.

These concerns have intensified as larger-scale, corporate growers have begun to dominate the organic industry, displacing the small, independent growers that have long provided most organic products. Companies like General Mills, Dean Foods, Kellogg, and Kraft have become some of the most powerful voices in the organic industry. Some of these companies are represented on the board that decides what substances should comprise the National List, a list of non-organic items that can be added to organic products without losing the organic label.

And the power of these large companies is threatening to reshape the organic industry in other ways. Recently, there’s been controversy surrounding the proposal of an organic checkoff tax program, which would require organic farmers and retailers with gross revenue over $250,000 to pay into a national marketing and research fund. The program would ostensibly use those funds to promote organic products, and is supported by large organic processors. But given that many thousands of farmers believe their checkoffs represent the interests of the largest, most powerful companies in their sector, organic farmers and retailers are concerned that the organic tax program would be more of the same.

One of the largest obstacles to expanding organic production has been supporting conventional farmers in transitioning their land to organic. It takes three years to transition a farm to organic production, calculated from the last time a prohibited substance was applied to the soil. The transition process requires financial investment, and can be challenging for farmers with legacies of conventional or commodity farming. As a consequence, even the largest companies in the organic sector are having trouble keeping up with demand for their products. Attempting to enrich their supply chain, some organic companies are buying up cropland to grow their own crops.

Even the most conventional food companies are looking to organics for its market potential. Monsanto is getting into the organic game, using its technological advantage to cross breed, but not genetically modify, superior vegetables. The agrochemical giant is hoping to appeal to consumers who are squeamish about genetically engineered food, but can’t afford pricey organic produce. Monsanto has a leg up on smaller producers who use more traditional methods to select for the best crops. If their project is successful, the future of organic produce may move even further from its back-to-the-land roots.